Don’t Buy the Wrong Marketing Tech

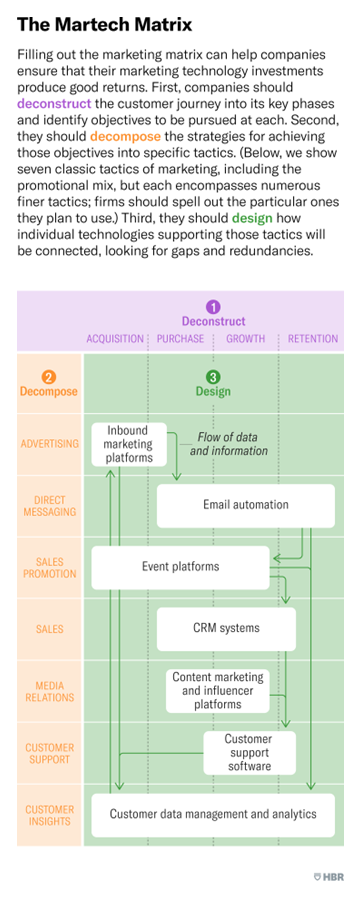

The number of vendors offering marketing tech is exploding, but too many companies take a “bottom-up” approach to purchasing it: Rather than starting with the objective of solving a problem, they begin with what is being sold to them. As a result they waste money on hoarding data they don’t need and on “shiny new objects”—tools that seem dazzling but don’t provide real insights or work with a firm’s other technologies. The solution? Follow the three D’s: Deconstruct the customer journey into key phases and choose objectives for each, decompose the marketing strategy for the objectives into tactics, and then design how the technologies supporting those tactics will function as a system, looking for gaps and redundancies.

A conglomerate hoping to improve sales conversions signed on with a third-party software platform that promised to generate and prioritize new leads. But the salespeople found that the leads it gave them were low quality and that it didn’t work well with their other sales tools. So instead they focused on selling to existing customers, which was easier and more productive. After considerable time and expense, the platform was abandoned, and the sales team was left wondering what to do next.

At another firm an executive who attended a software conference became enamored with one exhibitor’s web-based content management system, which produced stunning data visualizations. So he bought the off-the-shelf product for his company’s website to use, believing his colleagues would be excited to adopt it. Yet he’d failed to consider how it worked with other technologies in the organization. In the end the purchase was a waste of several hundred thousand dollars, and the solution was replaced with another one that integrated with the firm’s systems more seamlessly.

A third firm contracted a vendor to build a customized central platform that could extract insights from data on customer behavior. The team that had hired the vendor gloated about the size and mix of the data—but couldn’t provide the chief marketing officer with any insights that improved the business. Over time this system too was scrapped.

These disguised vignettes are all actual examples of how marketing technology is failing companies, drawn from our interviews with senior marketing technology managers.

Marketing technology, or “martech,” has become ubiquitous and necessary. By sourcing, archiving, and integrating customer information and feeding it into algorithms, martech can greatly increase marketers’ efficiency. It has already revolutionized advertising, content marketing, sales management, and commerce. The CMO Council reports that nearly 70% of its members are increasing their investments in marketing technology, and according to BDO, WARC, and the University of Bristol, martech is a $122 billion industry that’s growing by 22% year over year. Venture funding and subscription-pricing models are inspiring entrepreneurs to launch more martech start-ups. The number of new entrants in 2019 alone nearly equaled the size of the entire industry in 2015. Meanwhile, tools that allow customers to integrate services the way children snap together Legos are leading more companies to sign on to new offerings each month.

So why isn’t martech working for so many firms?

In this article we first outline two key pitfalls: data hoarding and the shiny new object syndrome. These errors are compounded by the larger problem of making decisions in a bottom-up manner, whereby the availability of systems and data drive the use cases chosen instead of the use cases’ driving the data and tools chosen. We then offer a top-down, strategic approach to managing the marketing technology stack—the set of data and vendor solutions—and provide an example of how it was used by a large software company to ensure success.

Data Hoarding and Shiny New Objects

Data hoarding—the acquisition and retention of information just because it might be of use someday and is close at hand—creates several problems. First, collecting hay to find needles is not very efficient. Worse, one might not even find the right needles. Consider a company that gathers information on every customer touchpoint, starting with the first inbound site visit, compiling years of data on transactions, location, web views, social media engagements, credit reports, driving records, and more. If a significant portion of that data is irrelevant, it will distract firms and get in the way of reaching more-important insights. Second, data hoarding is not goal directed—a problem that predictive artificial intelligence can’t solve. In the end managers wind up with the data they have instead of the data they need. Between the expense of acquisition and storage and the waste of time, the cost of data hoarding can be immense.

Martech is a $122 billion industry that’s growing by 22% year over year; 70% of CMOs are increasing their investments in it.

The shiny new object syndrome affects firms that sign on with vendors that offer intriguing tools, regardless of whether those tools will solve the firms’ specific problems. Martech tools come in two main forms—new applications and new methods—and both kinds can fall short. For example, there is an endless stream of new customer segmentation applications (commonly called customer profiles or personas), but many tell companies nothing about how responsive different customers will be to marketing. Likewise, there’s a growing array of methods such as machine learning and AI tools, but their applicability and performance vary considerably across uses, industries, and even time. Often they come with a variety of interfaces and dazzling graphics that aren’t always helpful. A word cloud of brand mentions on social media, for example, says little about whether those mentions are made by target prospects. A better approach is to first consider the touchpoints where targets engage and then look for methods and data that tap into them.

What do data hoarding and the shiny new object syndrome have in common? Both have a bottom-up instead of a top-down focus. That is, rather than starting with the objective of solving a business problem—such as how to drive customers along the path to purchase—they begin with what is available or being sold to the company. Bottom-up approaches often result in tools and data that are either misaligned with the business objective or unable to provide insights that are relevant to it. As a result, the marketing technologies ultimately wind up unused and neglected. They become junk.

Moving Toward a Top-Down Approach

Creating a top-down marketing stack involves a three-step framework we call the three D’s: deconstructing the customer journey, decomposing the marketing strategy into tactics, and designing the martech stack.

Deconstruct. First, you need to break down the customer journey into its major phases, from the initial customer contact to post-sales activities, and for each phase define a desired outcome and metrics for assessing it. At the start of the journey, for example, you might focus on awareness and assess it through customer surveys or numbers of site visits. At the end you might focus on satisfaction and measure it through mentions on social media or product returns. Decompose. Next, you must take your desired outcomes and break your strategies for achieving them down into core tactics. Ultimately, it is these tactics that marketing technology will seek to scale up or automate. Say you want to increase customer awareness; a good tactic for doing that is inbound marketing. A good tactic for increasing satisfaction, on the other hand, is to enhance the customer experience through superior site content or operations. Design. Once the marketing team has defined its core tactics, it’s time to decide which tools can be used to support each one. For this task, we recommend something we call the Martech Matrix. It maps out which tool is designed to support which tactic and makes clear how the tools should work together.

Until recently, managers could keep track of how they were using marketing tech manually. But as martech tools have proliferated, managing them has become more complex. And without more-sophisticated coordination, martech failures are becoming more common. One example from our executive interviews involved a firm that used one product to manage event registrations and another for automating email distribution and customer databases. Though both products involved registration information, they couldn’t communicate and duplicated functions. Because of the lack of coordination, funds and time were wasted.

To avoid problems like this, managers need to recognize how interdependent the elements of the martech stack are. If any component in the stack fails, the whole system may crash.

The three-D, top-down approach has several key benefits. First, it’s proactive, not reactive. That improves efficiency and lowers costs. Second, it enables managers to spot holes and redundancies in their martech strategies. Third, it explains the martech structure to others in the organization. Teams designing a stack often have to endure spurious “alterations” proposed by vested interests. Our interviews suggest that it isn’t uncommon for managers to favor a particular technology without regard to how it integrates with other technologies. The articulation of martech as a system helps prevent this, because it highlights how the tools work together as well as areas of potential duplication.

Bringing It All Together

Besides making smart choices about which tools to use, managers must also build an internal case for adopting the martech strategy, create the right organizational structure to nurture it, and persuade others in the organization to deploy it.

Making the use case requires managers to consider two critical questions: (1) Will the data or answers we get from the technologies actually alter the decisions we make? And if so, (2) will the benefits be greater than the cost of implementing the technologies? If an advertising program, for example, remains the same once the firm has new ad data or tools, the utility of the technology is negligible. And even if the program changes, the return on investment might be so small that it’s not worth it.

Creating the supporting organizational structure is also challenging. Several years ago many marketing functions were hosted by IT because they were data-intensive and expensive. However, the landscape has evolved for several reasons. First, the cloud allowed data and software to be hosted off-site, obviating the need for large internal infrastructure investments, which are typically the purview of IT. Second, the pricing model for software has switched from purchases to subscriptions, or software as a service. That means firms need not make big up-front investments in software, which again was usually the job of IT. Third, application programming interfaces (APIs) have enabled disparate solutions to work together more efficiently. Internally developed solutions, however, often can’t tap into the broader ecosystem of marketing technology, so companies are choosing more tools developed by third parties, which are being managed by marketing and sales rather than IT. Because of this, many companies are now using hybrid matrix organizational approaches to manage these technologies. Each vertical function (such as marketing, sales, or support) has a person dedicated to its technology needs while a senior martech manager, who reports to the CMO, ensures that the tools used by all the functions work in a coordinated manner.

In a large organization, getting buy-in from internal stakeholders is also necessary for successful deployment. The intended users should have significant input into both the design of solutions and their implementation. The users need to feel that solutions will expedite and improve their work and be easy to employ. Second, there must be an organizational commitment to resourcing and training. Leaders often assume that their teams have the capacity and knowledge to adopt new technology. Dazzled by a shiny new user interface in a product demonstration, a leader sometimes mistakenly presumes a tool is simple to use, but many tools aren’t. Companies must ensure that employees are able to gain proficiency in the new technology.

How One Company Revolutionized Its Martech

To see how all this comes together, let’s examine Oracle’s experience.

In 2012, Oracle was shifting from selling products to selling services via the cloud. Its on-premises internal marketing capabilities and legacy technology were inconsistent with its new positioning and becoming obsolete. The integration of data across technologies at the company was incomplete and in some areas unfeasible. In one instance, redundant and incompatible online event technologies were adopted. Hundreds of thousands of customer data points were disorganized and disconnected. That limited Oracle’s ability to deploy technologies that were critical to its sales pipeline. Moreover, organizational silos separating sales, field marketing, product marketing, and corporate marketing led to inconsistent messaging and a fragmented customer experience.

Bottom-up approaches often result in tools and data that are misaligned with the business objective or unable to provide relevant insights.

As a result, Oracle was able to convert only 2% of marketing’s qualified leads into sales. Salespeople constantly groused about low-quality leads. “We had yet to convince the organization that we were having a financial impact on the business,” says Bence Gazdag, senior director of marketing technology. To turn things around, Oracle’s martech team followed the three-D approach:

- First, the team deconstructed the customer journey so that it could link the marketing technologies better to desirable outcomes. The outcomes it identified included generating awareness, enhancing engagement, driving purchases, and improving retention.

- Second, the team decomposed the associated marketing strategies into tactics that could be mapped against the customer journey, such as account-based marketing, which drives purchases by sending customers and prospects highly customized messages. That exercise revealed some new insights about which tactics could be automated—for instance, that AI trained on customer data could replace the laborious process of writing account-specific emails at scale.

- Next, the team designed the martech stack, by linking technologies to the marketing tactics used for each phase of the journey and mapping data flows across those technologies to ensure that they functioned as an integrated system. For example, tools used by the sales force had to communicate with account-based marketing products to ensure consistency in messaging. Neither could be chosen separately.

Though the transformation faced many potential roadblocks, it benefited from the firm’s attention to implementation. First, the use cases and financial benefits for the organization were clearly defined by senior management, thereby ensuring resource commitment. For example, the effort would not only improve Oracle’s own lead conversion rates but also strengthen its understanding of the needs of its own clients and how Oracle’s technology products could help them.

Second, a new organizational structure was put in place to manage the transition and beyond. Previously, the sales, field marketing, product marketing, and corporate marketing functions each managed its own technology. Now all martech is controlled by a centralized function in a new global marketing demand center reporting to the CMO, who holds weekly coordination meetings to ensure martech remains a strategic priority.

Finally, the team sold the martech innovations internally by targeting influencers and early adopters with high perceived expertise within the organization. Their support accelerated the embrace of martech among those in the middle of the adoption curve, while laggards on the slow end of the curve were reassigned to other roles or let go. The technology was also streamlined to make it easier to use. Meanwhile, the insights gained from deploying the three-D framework began helping Oracle sell its own technologies to its customers.

Today, Oracle has one of the most complete and efficient martech stacks in the world. It has high levels of use within the organization. Average transactions are 69% larger when marketing is involved. Seventy percent of the company’s customer-purchase experiences have been automated, which has helped double its opportunity-to-lead conversion rate and reduce the time it takes to initiate a marketing campaign from four weeks to five days. Marketing now handles 1.5 billion customer interactions yearly, up from 2 million. Moreover, opportunistic purchases of shiny new objects have largely disappeared, because new tools aren’t adopted if they don’t fit into the organizational strategy or with the system of existing technologies.

In light of its tremendous growth and adoption, marketing technology now commands the attention of every major organization. However, companies should realize the risks of buying too many third-party tools without enough coordination or a strategy for their use. The methods we’ve described here should help companies avoid data hoarding and the false promise of shiny new objects—and enable them to create a martech stack that’s more likely to drive sales up and costs down.

Responses